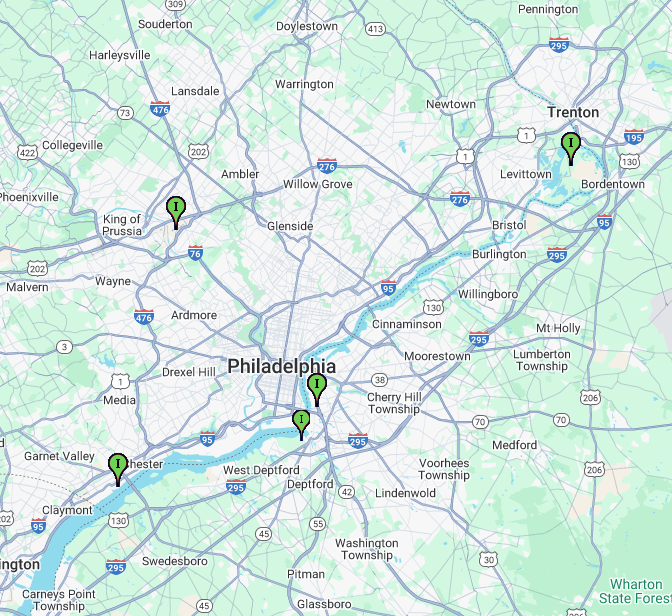

Philadelphia, the poorest big city in the nation,[1] is surrounded by five trash incinerators, the worst cluster of trash burners in the U.S.[2] These incinerators are five of the top seven industrial air polluters in Philly and its surrounding counties, according to EPA emissions data.[3]

37% of Philly’s trash is burned,[4] mostly in the nearby City of Chester in Delaware County, a famous case of environmental racism.[5] The Reworld (Covanta) trash incinerator in Chester is the largest in the U.S.[6] and is missing key pollution controls that limit toxic pollution.[7] It burns up to 3,500 tons of trash and industrial waste per day and is the #1 industrial air polluter in the region, contributing to Philly’s high asthma and cancer rates.[8],[9],[10] Over 2,400 tons of scrap tires that are “recycled” in Philly get incinerated in Chester annually, with more also being burned at Covanta’s incinerator in Plymouth Township, Montgomery County (by I-476 and Ikea).[11]

Is incineration preferred over landfilling? No. Incineration turns trash into harmful air pollution and toxic ash, which is landfilled. While landfilling threatens groundwater and air pollution, toxic chemicals are more contained and impacts are less wide-spread. Although methane rises from landfills (which can be reduced by diverting compostables), the climate impacts of incineration are greater and more immediate. Until we find ways to eliminate most waste, the better place for it is in a landfill, not in our atmosphere. The life cycle assessment conducted for Delaware County shows that burning trash in Chester and landfilling its toxic ash is 23% worse for the climate and 23 times as harmful for other health and environmental impacts than going directly to their landfill with unburned trash.[12] The internationally peer-reviewed definition of Zero Waste and the Zero Waste Hierarchy, codified by the Zero Waste International Alliance, are used for certification around the world and explicitly prohibit incineration in all forms.[13] Landfilling is the back stop after many upstream steps.

But EPA says incineration is preferred, and they’re the experts, right? Actually, no. EPA has long had an inverted triangle graphic called a waste management hierarchy (which is not the Zero Waste Hierarchy above) that places incineration (which they describe as “energy recovery”) over landfilling (described as “disposal,” as if incineration is not also a form of disposal).[14] However, in our February 2022 meeting with top staff in EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management, which is responsible for waste programs, they admitted that they have no documentation to support their placement of incineration above landfilling in their hierarchy. Since July 2022, EPA has had a disclaimer on their hierarchy stating that they are revisiting it.[15] This was stalled because EPA also must revisit a flawed climate model that they use called WARM, which was never peer reviewed until 2023 after we asked for such a review. EPA also opened a comment period,[16] but has not yet incorporated that feedback into the model, and it may be a few more years before that can happen. Before completing the process, the hierarchy disclaimer was removed by the Trump EPA on 12/19/2025 without revising the hierarchy.

Where will the waste go if we don’t burn it; aren’t we running out of landfill space? Pennsylvania has 43 landfills and six incinerators.[17] The state has such a glut of disposal capacity that it has taken waste from 44 states, plus DC, some U.S. territories, and other countries, and has been the largest importer of waste for around 35 years.[18] It may seem as if we’re running out of landfill space because landfills are given limited capacity permits, but the PA DEP constantly grants new permits for expansions.[19] See Philly’s specific alternatives outlined here: phillyzerowaste.org/alternatives.pdf

Will it cost more? Not necessarily. For Philadelphia, the costs are comparable. The city has two contracts, one with Waste Management (now just “WM”), handling 70% of the city’s trash, mainly via landfilling, and the other with Covanta (now “Reworld”) for the other 30%, which is all incinerated. As shown below, the contract prices are similar at around $65 per ton (with inflation built into the contracts, the rate is around $79.91/ton as of January 2026).[20] Both contracts run from 7/1/2019 through 6/30/2026. See more on cost concerns here: phillyzerowaste.org/cost.pdf

The per-ton 2019 prices in the current contracts are as follows:

Covanta (Reworld):[21]

58th St Transfer Station: $65.50 for first 120,000 tons per year, then $64

Chester Incinerator: $58.50 by transfer trailer; $57 by compactor truck

Plymouth Incinerator: $63.50 by transfer trailer; $59 by compactor truck

Residual waste: $65.50

Waste Management (WM):[22] $65.25

Same prices for delivery to the two transfer stations in the city (Philadelphia Transfer Facility and Recycling Center and the Forge Transfer Facility) or directly to Fairless Landfill or the Wheelabrator Falls Incinerator, both of which are in Falls Township, Bucks County.

Isn’t cheaper best? In addition to the contract prices, there are externalized health and environmental costs that show up in medical bills, and social costs like flooding and heat deaths. The calculated value of that damage is another $144/ton for landfill and $337/ton for incineration.12

Doesn’t methane from landfills make them worse? No. The total health and environmental impacts of incineration are worse than landfilling, even in worst-case scenarios where no landfill gas is captured.[23] Incineration immediately releases all the carbon into the atmosphere (even from plastics and wood) that, in landfills, mostly stays put and is sequestered. Composting food scraps and yard waste to prevent most landfill methane emissions is a better solution than burning the entire trash stream.

But if we have to truck it further to reach landfills, won’t the diesel truck emissions make it worse? No. Transportation impacts are so small relative to landfilling or incineration that one would have to drive a diesel truck to California and back to almost close the gap on how much worse incineration is compared to landfilling. This is documented in the life cycle assessments done for Delaware County, PA23 and even better illustrated in one done for Montgomery County, MD.[24]

Doesn’t switching the 37% we burn to landfills mean harming environmental justice communities? No. Landfills in PA are very much in rural, predominantly white communities, or in communities like Falls Township, Bucks County (where over half of Philly’s waste is landfilled) where no one lives within about two miles. It is the incinerator industry that has major environmental justice impacts, most disproportionately impacting African-Americans, such as the incinerator in Chester where over 17,000 people live within two miles and 69% are African-American, most of whom are low-income.[25] For more on the demographics of communities impacted by Philly’s trash: phillyzerowaste.org/demographics.pdf

Do Chester City residents want Philly’s trash? No. Residents of Chester have expressed their opposition many times over the years. However, two letters were used to justify the current contract with Covanta.[26] One was from former Chester City Mayor Thaddeus Kirkland, who signed a letter clearly written by Covanta.[27] Mayor Kirkland, after running the city into bankruptcy, is no longer in office. Current Mayor Stefan Roots is outspoken in opposition to the incinerator, and has publicly expressed that he’d like to see it gone.[28] The second letter was from Chester Environmental Partnership (CEP), an outfit run by a suburban reverend who does not even live in Chester and who has a signed agreement to take money from Covanta annually since 2006.[29] CEP regularly gives praise and awards to Covanta.

Delaware County does not want incineration, either.28 The county has relied on burning nearly all of their trash in Chester for many years, but since Democrats took control of the county, they changed over the Delaware County Solid Waste Authority board, and adopted a Sustainability Plan and a county Zero Waste Plan that actually follow the definition of Zero Waste by ending incineration.[30] The county’s goal is to end its use of incineration once they rebuild their two transfer stations. They have already started diverting 15% of their waste from the incinerator since 2023.

Do Philadelphia residents want to burn our trash? In 2019, 41 groups opposed the incineration contract, but were ignored.[31] All 11 people who gave public comment before city council that year in the hearing on the contract were opposed to the incinerator contract. In October 2023, the city council held its first hearing on whether the city should incinerate our waste.[32] Almost everyone who testified was a Philadelphia resident opposed to the contract and many specifically called for city council to pass legislation to ban city contracts for burn waste or recyclables, which (on 9/ 18/2025) was introduced by Councilmember Gauthier as the Stop Trashing Our Air Act.[33] Only one resident who lives in Chester spoke and she was in favor because Covanta gives donations to her nonprofit. Every other person who spoke, including a Montgomery County resident who lives near the malfunctioning Covanta Plymouth incinerator, were opposed to the incineration contract.

The Streets Department had testified to City Council in 2019 that the Philadelphia Office of Sustainability and the (now abolished) Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet “concluded that waste-to-energy is preferable over landfill for waste disposal.”[34] This was supposedly based on these offices having been named on a city waste plan where the EPA hierarchy was followed.[35] However, since this 2019 statement to City Council by the Streets Department, the Office of Sustainability has repeatedly denied having expressed support for incineration over landfilling.[36]

Do environmentalists favor incineration over landfilling? No. Groups that have evaluated the issue and expressed any opinion on it are opposed to incineration. Sierra Club[37] is probably the biggest name in this category, but there are many others as well.[38] There are some rare examples of environmental or liberal think tank groups who support incineration while taking repeated donations from Covanta.[39] Similarly, there is a City College of New York organization that publishes pro-incinerator research while taking money for many years from Reworld/Covanta and other incinerator companies.[40]

Is it legal for the city to ban incineration contracts? Yes. The city has the freedom to contract as a market participant and already uses that power to prohibit other sorts of contracts.

Does Philly have a legal obligation to end incineration? Yes. The PA Environmental Right Amendment[41], the duty to look after the health, safety and welfare of our residents, and Title VI of the Civil Right Act, which prohibits recipients of federal funds, such as the City of Philadelphia, to take actions which have a discriminatory impact (regardless of intent) on protected classes of people such as racial minorities living in the City of Chester.[42]

For more information, please contact Mike Ewall, Esq., 215-436-9511 or mike@energyjustice.net

[1] Of the 10 largest U.S. cities: https://www.inquirer.com/politics/philadelphia/philadelphia-poverty-rate-decline-household-income-20240912.html

[2] https://ejmap.org/jtiny=5048 (analysis includes clustering, as displayed on this map, as well as factoring in the amounts of waste burned)

[3] 2000 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Emissions Inventory. https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/national-emissions-inventory-nei

[4] 2024 data from PA DEP Waste Database. http://cedatareporting.pa.gov/reports/powerbi/Public/DEP/WM/PBI/Solid_Waste_Disposal_Information

[5] See http://www.delcoej.org and for environmental racism generally, http://www.ejnet.org/ej

[6] Operating U.S. Trash Incinerators ranked by size. https://energyjustice.net/incineration/usplants/

[7] Of 62 operating trash incinerators in the U.S., this is one of four with no carbon injection system to capture and move highly toxic dioxins and mercury from the air to the ash. (Energy Information Administration Form 860 data.) The incinerator has also lacked controls for nitrogen oxides (NOx) that trigger asthma attacks and finally installed them in 2025 after 34 years of operation, reducing these emissions by only 21%. Modern controls would reduce NOx by 70-80%.

[8] Their status as #1 industrial air polluter is based on EPA data (see footnote 3).

[9] In 2025, Philadelphia was ranked as the 4th worst “asthma capital” in the nation by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. The city is consistently in the top ten each year. See: https://aafa.org/asthma-allergy-research/our-research/asthma-capitals/

[10] Philadelphia has the 2nd worst cancer incidence among the counties hosting the ten largest cities in the U.S., based on 2017-2021 data from the National Cancer Institute. https://www.statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/incidencerates/

[11] Covanta Delaware Valley 2023 Listing of Quarterly Residual Waste Generators, PA Department of Environmental Protection.

[12] Dr. Jeffrey Morris, Sound Resource Management Group, Inc. “Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Monetization for Nine Human and Environmental Health Impacts from Delaware County, Pennsylvania MSW Diversion & Disposal 2020 Baseline and Recommended Zero Waste Plan,” June 2023. See overview and summary charts at http://www.phillyzerowaste.org/LCA.pdf and the full study at https://energyjustice.net/incineration/DelcoLCA.pdf

[13] Zero Waste International Alliance, Zero Waste Definition: https://zwia.org/zero-waste-definition/; Zero Waste Hierarchy: https://zwia.org/zwh

[14] EPA Waste Hierarchy. https://www.epa.gov/smm/sustainable-materials-management-non-hazardous-materials-and-waste-management-hierarchy

[15] Id. The disclaimer stated: “EPA is now in the process of reviewing the waste hierarchy to determine if potential changes should be made based on the latest available data and information.” See archived copy with the disclaimer.

[16] See comments in docket here: https://www.regulations.gov/docket/EPA-HQ-OLEM-2023-0451, including extensive comments by Energy Justice Network and other experts here: https://www.regulations.gov/comment/EPA-HQ-OLEM-2023-0451-0112 and here: https://www.regulations.gov/comment/EPA-HQ-OLEM-2023-0451-0084

[17] PA Department of Environmental Protection, Municipal Waste Landfills and Resource Recovery Facilities.

https://www.pa.gov/agencies/dep/programs-and-services/business/municipal-waste-permitting/mw-landfills-and-resource-recovery-facilities.html

[18] Find copies of Congressional Research Service reports on Interstate Shipment of Municipal Solid Waste dating back to the 1990s here: https://actionpa.org/waste/

[19] The PA Department of Environmental Protection will not accept a landfill expansion permit from a landfill unless it has under five years of projected capacity remaining. This helps ensure that there is an ongoing perception of “running out of space” for decades, yet expansion permits are routinely granted. See: 25 Pa. Code § 271.202.(f) https://www.pacodeandbulletin.gov/Display/pacode?file=/secure/pacode/data/025/chapter271/s271.202.html

[20] Per Scott McGrath, Phila. Sanitation Department’s Environmental Planning Director at 1/15/2026 Solid Waste and Recycling Advisory Committee Meeting.

[21] Current Philadelphia City waste disposal contract with Covanta (2019-2026): https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/2019CovantaContract.pdf

[22] Current Philadelphia City waste disposal contract with Waste Management (2019-2026): https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/2019WMContract.pdf

[23] See this chart: https://www.energyjustice.net/incineration/LCA.pdf#page=7; see footnote 12 for the full study, a very detailed life cycle assessment conducted for Delaware County, which assumes the worst global warming potential for methane (86x that of CO2 over 20 years).

[24] Life Cycle Assessment summary chart from “Beyond Incineration: Best Waste Management Strategies for Montgomery County, Maryland,” March 2021. https://www.energyjustice.net/incineration/LCA.pdf#page=3

[25] Analyses from https://www.ejmap.org, https://www.ejmap.org/justice/, https://www.energyjustice.net/incineration/ej, and EJ Analyzer Tool

[26] Philadelphia City Council Streets Committee Hearing Transcript, 6/5/2019. https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/2019-06-05transcript.pdf#page=20

[27] Letter from Chester City Mayor Kirkland to Philadelphia Councilmember Squilla, 5/31/2019. https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/KirklandLetter.pdf

[28] Mayor Roots has consistently opposed the incinerator. See his 2021 guest opinion piece, and this 2022 news article. See also the recent letters from Mayor Roots and other Chester City and Delco officials supporting the Stop Trashing Our Air Act at https://phillyzerowaste.org/delcosupport.pdf

[29] https://delcoej.org/pdf/2019-CEP-Philly-Letter.pdf See Covanta’s history with CEP and funding agreement at: https://delcoej.org/cep

[30] “By adopting the Zero Waste approach, the [Sustainability] Plan seeks to move away from incineration and other harmful practices that threaten the environment or public health.” https://delcodev.ntc-us.com/news/delaware-county-commits-greener-future-release-its-5-year-sustainability-plan

[31] 40 Organizations call on Mayor Kenney to Stop Burning Philly’s Trash (plus separate letter from American Sustainable Business Council). https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/

[32] Philadelphia City Council Committee on the Environment Hearing 10/25/2023. https://youtu.be/5Aw2Xfk7fQA?feature=shared&t=1622

[33] Stop Trashing Our Air Act, bill #250768. https://phila.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=7664636&GUID=9A3DD83A-92D8-44CD-A996-0D4267096262

[34] Philadelphia City Council Streets Committee Hearing Transcript, 6/5/2019. https://phillyzerowaste.org/contract/2019-06-05transcript.pdf#page=8

[35] Philadelphia Zero Waste and Litter Action Plan. https://www.phila.gov/media/20190821131753/Zero-Waste-Litter-Action-Plan-2017.pdf#page=6;

Our appeal of our Right-to-Know Law request established that this plan is the source of then-Streets Commissioner Carlton Williams’ statement representing to City Council the positions of other city offices as if they had researched and taken a position that they had not taken.

[36] Personal communications with then-director of the Office of Sustainability, Christine Knapp.

[37] “Sierra Club Zero Waste Policy opposes any form of combustion of wastes, and the definition of incineration in the policy lists included technologies.” https://www.sierraclub.org/zero-waste-guidance-destructive-disposal

[38] 274 organizations write to Biden White House to oppose EPA preferences for incineration: https://energyjustice.net/incineration/2022CEQletter.pdf

[39] Center for American Progress (CAP) was cited by the Streets Department as a source justifying the city’s support of incineration. CAP accepted $50K to $100K in annual donations from Covanta from 2013-2021 after publishing this 2013 report supporting incineration: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/energy-from-waste-can-help-curb-greenhouse-gas-emissions/

[40] Waste-to-Energy Research and Technology Council. “WtERT’s Global Memberships and Affiliations.” http://www.wtert.org/partners/

[41] Article 1, Section 27 of the Pennsylvania Constitution provided the people a constitutional right to clean air, which every Pennsylvania municipality is obligated to maintain for the benefit of all the people. https://www.legis.state.pa.us/WU01/LI/LI/CT/HTM/00/00.001.027.000..HTM. Read the Pennsylvania Supreme Court case that spelled out these rights and municipal obligations here: https://johndernbach.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/83_A.3d_901.pdf

[42] Ewall, M. “Legal Tools for Environmental Equity vs. Environmental Justice.” https://www.ejnet.org/ej/SDLP_Ewall_Article.pdf